Business Aviation Weather: Understanding Ceiling Conditions

Ceiling conditions—referring to the height of a cloud base above the ground—can significantly impact business aviation operations. Low ceilings may trigger delays, diversions, or missed approaches, particularly in areas with challenging terrain or limited alternate airport options. How ceilings affect your operation depends on the type of flight, operator SOPs, pilot qualifications, and comfort level.

Here’s what you need to know when evaluating ceiling conditions for your next mission.

Ceiling Requirements Vary by Operator and Flight Type

Minimum ceiling requirements are not one-size-fits-all. They vary depending on factors such as:

- Crew experience and preferences

- Flight department SOPs

- Local airport and terrain considerations

For example, one operator may be comfortable with a 3,000-foot ceiling minimum, while another might require a more conservative threshold.

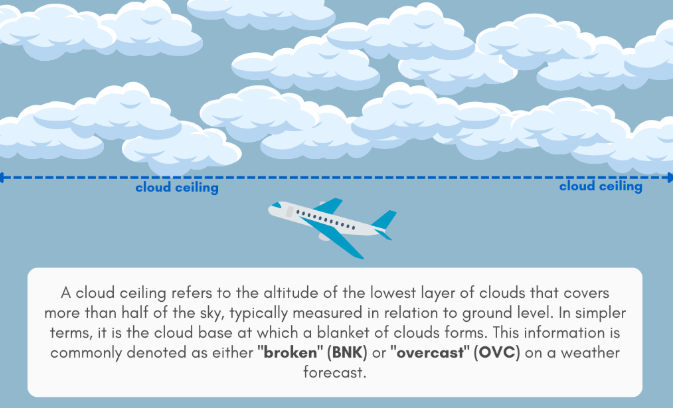

What Defines a Ceiling

In aviation, “ceiling” refers to:

In aviation, “ceiling” refers to:

- The lowest broken (BKN) or overcast (OVC) cloud layer reported at the airport

- In cases of total sky obscuration, vertical visibility is used as the ceiling

Forecasting changes to ceilings often includes other factors such as incoming fog or weather systems, so your weather provider should always offer context—not just numbers.

How Cloud Cover and Ceilings Are Measured

Cloud cover is categorized using standard aviation codes:

- SKC: Sky clear (0/8)

- FEW: Few clouds (1–2/8)

- SCT: Scattered (3–4/8)

- BKN: Broken (5–7/8)

- OVC: Overcast (8/8)

Automated Weather Observing Systems (AWOS) and certified human observers work together at many airports to determine accurate ceiling reports. While AWOS provides useful real-time data, experienced observers often offer more nuanced assessments—especially in rapidly changing or borderline conditions.

Minimum Ceiling Requirements and Regulatory Constraints

For charter operations (Part 135), ceiling requirements are more restrictive:

- Operators must use official government forecasts (e.g., TAFs and METARs)

- This can sometimes force diversions, even when actual weather appears acceptable

- Part 91 (private, non-revenue) operators have more flexibility in their choice of forecast sources and operating decisions

Certain airports also publish recommended minimums (e.g., 800 ft ceiling / 2 miles visibility), but these are not always mandatory. Still, operators must weigh these guidelines carefully, especially in unfamiliar or complex environments.

How Ceiling Height Is Determined

Forecasting ceiling height involves multiple tools:

- METARs for current observations

- TAFs for short-term forecasts

- PIREPs from other pilots in the area

- Satellite imagery and weather model data

Keep in mind: forecast accuracy improves significantly within 24 hours of flight. While long-range predictions can help with early planning, last-minute updates are essential for decision-making.

Also note that in some regions, you may face limitations in accessing or interpreting weather data. For example, in parts of South America, forecasts may only be available in Spanish or Portuguese.

Alternate Airport Planning

Ceiling conditions play a key role in alternate planning. If weather at your primary destination is forecast to fall below minimums, your alternate must meet or exceed planning thresholds.

- In large countries like China, Russia, or Canada, alternates may be few and far between

- Equal time point (ETP) considerations may also raise your required ceiling minimums

- When ceiling drops below alternate planning minimums, the airport is no longer valid for alternate use

While 800/2 is often used as a planning minimum (based on Part 135), each flight must be evaluated individually, and the pilot in command makes the final call.

Operating in Remote or Data-Sparse Areas

In remote regions, official weather reports may be limited or non-existent. In these cases, your forecaster may rely on:

- Satellite data and model outputs

- Terrain and elevation profiles

- Upper-air soundings and moisture patterns

- Regional climatology and neighboring observations

It’s important to recognize the limitations of available data and factor in conservative margins for your planning.

Seasonal and Regional Ceiling Considerations

Certain locations are known for persistently low ceilings due to seasonal or environmental factors:

- Parts of India and China may remain under IFR conditions for extended periods due to haze or agricultural smoke

- Coastal regions and islands often experience early morning fog or marine layers that lift with the sun

- London-area airports frequently contend with fog during specific times of year

A good forecaster will incorporate seasonal trends and historical data when predicting ceilings in these locations.

Timing Your Forecasts

Weather changes quickly, and ceiling forecasts are no exception. For the best results:

- Use general forecasts 72 to 48 hours before departure for broad planning

- Refine your assessment with updated forecasts within 24 hours of the operation

- Get final confirmation just prior to takeoff, especially when conditions are marginal

Preliminary weather briefs can help frame your planning discussions, but detailed updates closer to departure are essential to avoid operational surprises.

Conclusion

Ceiling considerations are not just about numbers—they’re about context. Terrain, alternates, seasonal conditions, and your team’s risk tolerance all play a role in setting appropriate minimums. Always work closely with your certified meteorologist to get an accurate and timely picture of expected ceiling conditions, and make sure your service provider is aligned with your operational thresholds.